The Rise and Fall of the Spa Hotel in Palm Springs

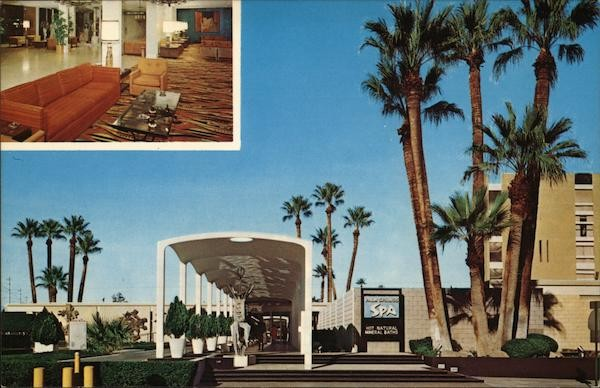

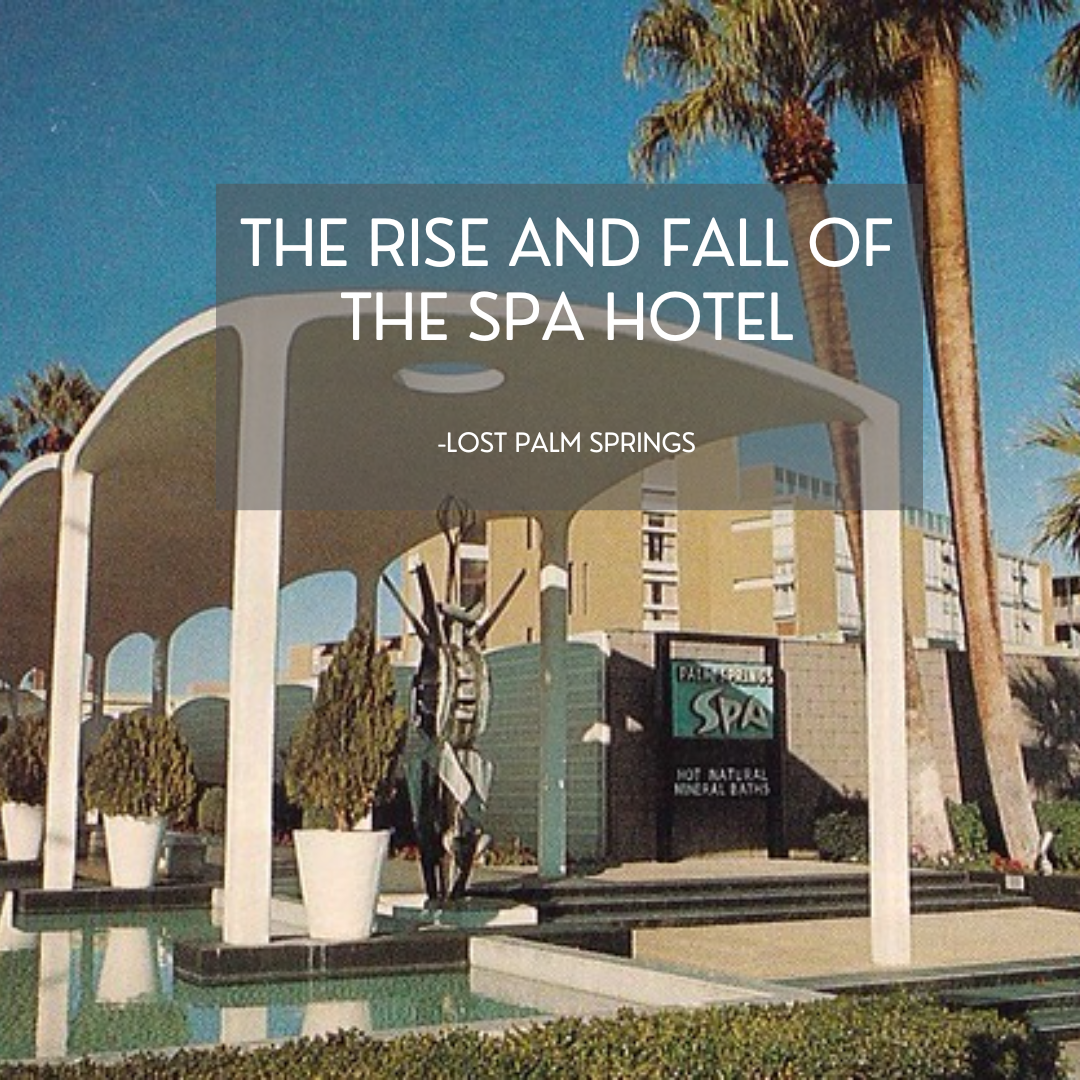

*Photo Credit: Palm Springs Spa Hotel colonnade and reflecting pool with Dancing Water Nymphs sculpture, vintage postcard, c. mid-1960s Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society Originally published as a commercial postcard Lost Palm Springs: The Rise and Fall of the Spa Hotel

Hot springs, modernist bravado, a floating colonnade—and a demolition that stunned the city of Palm Springs.

Palm Springs has lost many midcentury landmarks, but few carried the symbolic weight—or emotional charge—of the Agua Caliente Spa and Hotel, more commonly known as the Spa Hotel. This was not simply a hotel and bathhouse. Rising above the ancient hot mineral spring that gave Palm Springs its very name, it was a civic statement—and now, another entry in Lost Palm Springs, a place deeply cherished by residents and no longer part of the city’s landscape.

For decades, the Spa stood at the intersection of architecture, tourism, civic life, and tribal land—making its eventual demolition one of the most debated and mourned architectural losses in the city’s history.

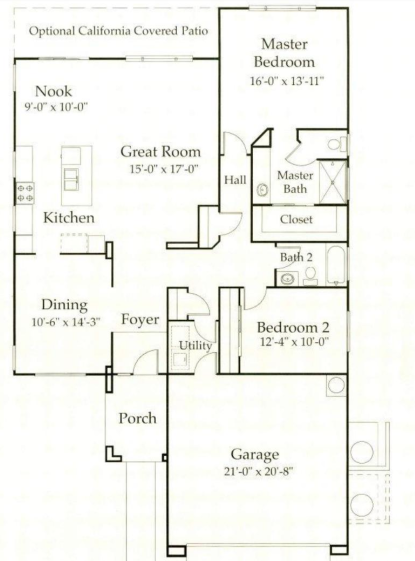

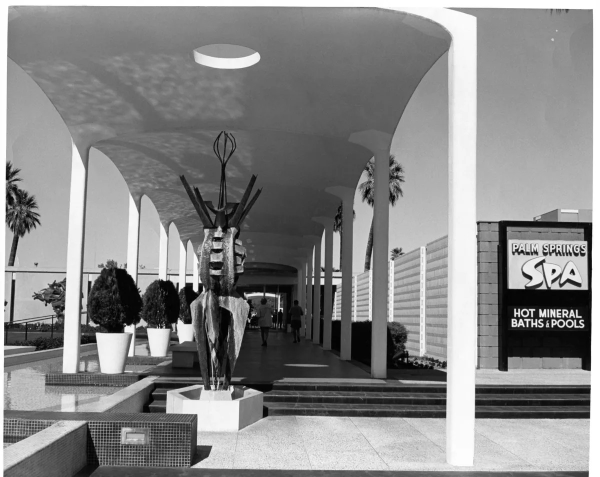

Palm Springs Spa Hotel colonnade and entrance sequence, c. early 1960sCourtesy of Palm Springs Historical SocietyOriginally published in Palm Springs LifePhotographer unknown

Built on the spring that started it all

The modern Spa Hotel story begins with a pivotal midcentury shift. The General Leasing Act of 1955 made it possible for new development partnerships to occur on tribal land. In Palm Springs, this led to the lease of an eight-acre parcel in the heart of the Agua Caliente reservation to developer Samuel Banowit and Palm Springs Spa Inc., a decision approved by an all-female Agua Caliente Tribal Council.

The project did not begin as a single-architect vision. Instead, it emerged from a developer-led collaboration, shaped by both civic ambition and the technical complexities of building directly atop the historic hot mineral spring. As landowner and steward of the sacred spring, the Tribe played a central role in approving the development framework, while the design and execution were overseen by the private development team.

A Midcentury Architectural Collaboration

The Spa Bathhouse and Hotel was the result of a rare and ambitious collaboration among some of Palm Springs’ most influential modernist architects, most frequently credited as William Cody, Donald Wexler, Richard Harrison, and Phillip Koenig. Each brought a distinct design sensibility shaped by the desert, yet they shared a core belief: architecture in Palm Springs should do more than shelter—it should orchestrate experience.

By the early 1960s, Palm Springs had become an international laboratory for modern design, but much of that experimentation played out in private homes. The Spa was different. This was civic-scale modernism, intended to be encountered by residents, visitors, and tourists alike. The architects understood the site’s significance—not merely as prime downtown real estate, but as sacred ground tied to the city’s origins.

Julius Shulman with an assistant on the top of the Spa Resort Hotel in Palm Springs.

Courtesy Of Michael Stern /The Desert Sun July 9, 2014

Rather than commissioning a single architect, Banowit assembled a group of architects already working at the forefront of Palm Springs modernism, each selected for specific expertise. This approach was not uncommon for large, technically complex projects of the era—particularly those combining hotel design, health facilities, and ceremonial public space.

William Cody, widely known for his mastery of resort and hospitality architecture, is often credited with shaping the overall architectural vision of the Spa Hotel and bathhouse. Donald Wexler, known for his focus on adapting to the climate and designing for the community, helped create plans and building methods that were ideal for a public space. Richard Harrison and Phillip Koenig are most often associated with design development, detailing, and coordination—especially critical for a site requiring careful circulation, open-air transitions, and integration with water features.

This was not a routine resort commission. Climate, movement, and spectacle were central to the design thinking. The Spa was conceived as a total environment, where architecture, water, landscape, art, and circulation worked together. From the moment visitors arrived, they were guided through a carefully choreographed sequence—approach, procession, and immersion—mirroring the ritual of bathing itself.

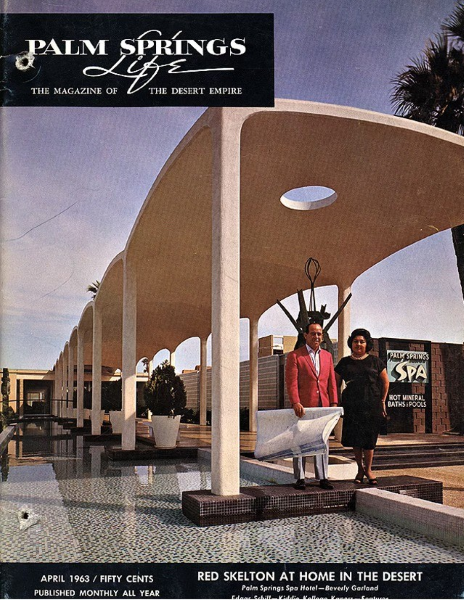

The iconic concrete-domed colonnade of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel, photographed for the April 1963 cover of Palm Springs Life. The image captured the Spa at its peak—where architecture, water, and civic identity converged at the heart of downtown Palm Springs.Photo by Slim Aarons, courtesy of Palm Springs Life.

Concrete was used boldly and unapologetically, not as decoration but as structure and sculpture. Open-air passages made it hard to tell where the inside ended and the outside began. Water reflected light and sky, reinforcing the ever-present connection between the built environment and the mineral spring below. Every element reinforced the idea that this place was not simply a destination but an experience unfolding in time.

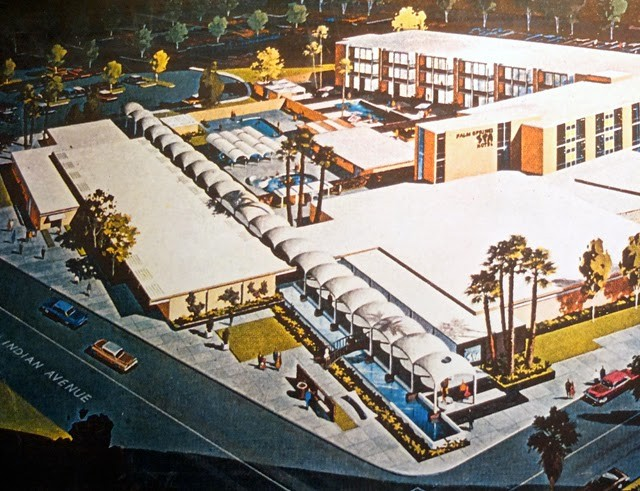

Completed in 1963, the project was ambitious and highly visible. It included a full-scale mineral spa built directly over the hot spring and a 131-room hotel rising three stories. Later, two additional stories were added, making it one of the tallest buildings in Palm Springs at the time. The Spa was designed to be both a destination and a declaration: a modern city embracing its origins.

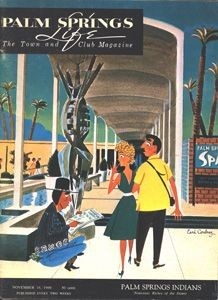

A stylized illustration of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel colonnade on the cover of Palm Springs Life, capturing how the Spa quickly became a graphic and cultural icon—its architecture recognizable enough to symbolize the city itself.Illustration by Earl Newman, courtesy of Palm Springs Life.

In many ways, the Spa represented the architects’ shared belief that modernism could be public, sensual, and theatrical, without sacrificing clarity or purpose. It stood as a confident statement that Palm Springs modernism wasn’t limited to glass houses tucked into quiet neighborhoods—it could also define the civic heart of the city.

That ambition is precisely why its loss continues to resonate today.

Water Before Architecture

Long before the Spa Hotel rose in downtown Palm Springs, mineral water shaped the destiny of the desert. Fed by aquifers flowing from the Little San Bernardino Mountains, across the Mission Creek Fault, and down from the snow-laden San Gorgonio Mountains, these hot and cold mineral waters created rare oases in an otherwise arid landscape.

The early Agua Caliente Bath House, photographed in the early 1900s, long before the modern Spa Hotel complex was built. Images like this document the original use of the hot mineral spring that would later anchor Palm Springs’ civic spa tradition.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society.

For the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians—whose name translates to “hot water”—the Palm Springs mineral spring beneath the Spa Hotel site was sacred. Tribal history holds that Cahuilla shamans used the spring for healing and spiritual renewal, believing its waters were connected to powerful underground forces that required respect, prayer, and offerings. Early California writer J. Smeaton Chase described it as “a natural water source in an otherwise hostile environment.”

Palm Springs Spa Hotel colonnade and bathhouse, c. early 1960sPhoto courtesy of Palm Springs Historical SocietyPublished in The Desert Sun, September 4, 2014

By the early 20th century, mineral springs across the Coachella Valley were drawing national attention, with bathhouses in nearby Desert Hot Springs attracting thousands of visitors seeking cures and rejuvenation. With a distinct civic ambition, Palm Springs pursued a similar path. When the Spa Hotel opened in 1963, it was built directly over the same sacred spring—transforming an ancient healing site into a modern public spa and architectural landmark.

A place where water, wellness, and ritual converged, the Spa Hotel's mineral baths represented a continuation of this long tradition. Though the architecture is now gone, the spring itself endures, anchoring both the memory of the Spa Hotel and the modern Spa at Séc-he to thousands of years of cultural and healing history.

The Spa Hotel: Design, Experience, and Daily Life

While the Spa Bathhouse and colonnade often receive the most attention, the hotel itself was an essential part of the Spa complex’s identity. Completed in 1963 alongside the bathhouse, the 131-room Spa Hotel was designed to work in concert with the mineral springs below—physically, visually, and experientially.

At three stories tall, the hotel stood out in a city still largely defined by low-slung buildings. Its vertical presence was intentional. Rising above the bathhouse and public spa spaces, the hotel signaled that this was not just a day spa but a full destination resort, where guests could immerse themselves in the Palm Springs spa lifestyle over days or weeks.

Early architectural rendering of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel and Bathhouse complex, illustrating the original design intent—including the iconic concrete-domed colonnade, bathhouse, and three-story hotel—prior to construction in 1963.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

Architecture shaped by climate

The hotel’s design reflected core midcentury desert principles: shade, airflow, and indoor–outdoor living. Guest rooms were oriented to maximize light while minimizing heat gain, often opening to balconies or shared exterior corridors that encouraged movement and cross-ventilation. Deep overhangs and recessed windows helped shield interiors from the harsh desert sun.

Rather than sealing guests inside, the hotel encouraged a constant relationship with the outdoors—views of the San Jacinto Mountains, the pool, and the surrounding civic spaces reinforced the feeling that the desert itself was part of the experience.

Guests enjoying the Palm Springs Spa Hotel pool, with exterior corridorsand balconies overlooking the courtyard—an example of the hotel’s midcenturyindoor–outdoor design and emphasis on climate-responsive living.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

A complement to the bathhouse

Importantly, the hotel was never meant to compete visually with the bathhouse or colonnade. Its massing was restrained and deliberately secondary, allowing the sculptural public spaces below to remain the architectural stars. This hierarchy was intentional: the spring and the communal spa experience came first, accommodations second.

Guests flowed easily between hotel rooms, pool areas, the colonnade, and the mineral baths, reinforcing the idea that the Spa was a continuous experience, not a collection of separate buildings.

The Palm Springs Spa Hotel shortly after its 1963 opening, showing the modern porte-cochère and three-story hotel wing designed as part of the city’s most ambitious civic-scale spa complex.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

Interiors and atmosphere

Inside, the Spa Hotel embodied midcentury resort restraint—clean lines, durable materials, and an emphasis on comfort rather than ornament. Public areas such as the lobby and lounges were designed as social spaces, places to linger between soakings or meet fellow guests drawn to Palm Springs for health, leisure, or escape.

An interior glimpse of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel bathhouse, where midcentury modern design emphasized calm, ritual, and wellness—combining indoor plantings, textured materials, The design featured open circulation to create a smoother transition from the city to the spa.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

The atmosphere was relaxed but aspirational, reflecting a period when spa culture blended wellness with glamour. Visitors included everyday travelers as well as celebrities, reinforcing Palm Springs’ image as both accessible and glamorous.

The Spa Hotel’s on-site beauty salon, reflecting the era’s emphasis on wellness, grooming, and resort living—where spa culture extended beyond soaking to full-service self-care.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

A changing role over time

As Palm Springs evolved, so did the Spa Hotel. Over the decades, renovations, operational changes, and the rise of casino-related development altered both the hotel’s appearance and its role within downtown. What had once been a carefully balanced modernist ensemble gradually became more difficult to read architecturally.

Palm Springs Spa Hotel guest room overlooking the pool, c. 1960sCourtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / published via Palm Springs LifePhotographer unknown

By the early 21st century, preservationists noted that while the hotel and bathhouse still retained significant midcentury character, later modifications obscured the original design intent—contributing to debates about feasibility, integrity, and reuse.

Why the hotel mattered

The Spa Hotel mattered because it represented something rare in Palm Springs history: a publicly visible, civic-scale modernist hotel tied directly to the city’s origin story. Unlike private estates or gated resorts, both residents and visitors experienced this architecture—a place where Palm Springs showcased itself to the world.

Its loss wasn’t just the loss of a building. It was the disappearance of a moment when Palm Springs believed that modern design, public space, and shared ritual could coexist at the heart of the city.

The colonnade: architecture as experience

If the Spa had a soul, it lived in the colonnade.

Palm Springs Spa Hotel colonnade and reflecting pool, c. 1963Photograph by Julius ShulmanCourtesy of the Julius Shulman Photography Archive / Getty Research Institute

And then there was the colonnade—a rare piece of public architecture that made people feel something before they ever reached the front door. The entrance sequence was defined by a dramatic, diagonal procession of repeating concrete domes, guiding visitors toward the bathhouse and mineral spring. Rather than a straight or utilitarian path, the architects designed a processional experience—one that slowed visitors down and framed views of sky, water, and mountains along the way.

As documented in preservation accounts and contemporary commentary, the colonnade transformed a simple walk into a moment of ceremony. It embodied a core midcentury belief: architecture wasn’t just about function—it was about how a place made you feel.

The structure also captured Palm Springs modernism at its best. The concrete felt permanent and grounded, yet the rhythm of the domes and open sides gave it a surprising sense of lightness. In a downtown that often feels like a collage of eras, the spa’s colonnade once felt cohesive, confident, and unmistakably Palm Springs.

Palm Springs Spa Hotel entrance and colonnade with inset interior view, vintage postcard, c. mid-1960sCourtesy of Palm Springs Historical SocietyOriginally published as a commercial postcard and later reproduced in Palm Springs Life

For many Modernism Week enthusiasts and preservationists, the loss of the colonnade still resonates because it represented something increasingly rare: civic-scale modernism—not a private home, not a gated resort, but a public place where architecture, art, water, and ritual came together in the open heart of the city.

The Sculpture: Dancing Water Nymphs

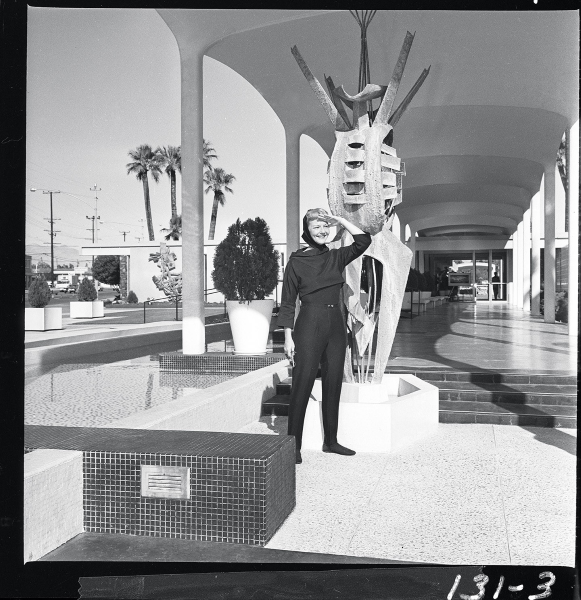

Complementing the architecture of the spa complex was one of its most memorable artistic elements: Dancing Water Nymphs, a bronze sculpture by Bernard Zimmerman.

Zimmerman was a well-known Southern California sculptor whose work frequently explored movement, rhythm, and the human figure—often at a civic or architectural scale. His sculptures were designed to be experienced in space, not viewed passively, making him a natural choice for a project as theatrical and processional as the Spa.

Bernard Zimmerman’s Dancing Water Nymphs positionedbeneath the iconic concrete-domed colonnade at the Palm Springs Spa Hotel. Early photographs like this confirm the sculpture’s original placement along the ceremonial entry sequence before it was later relocated to the center fountain.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

Commission and intent

Dancing Water Nymphs was commissioned specifically for the Spa complex as part of its original midcentury vision, when architecture, art, and landscape were conceived as a unified whole. Like the building itself, the sculpture drew directly from the site’s relationship to water—its flowing forms evoking the mineral spring beneath and reinforcing the ritualistic nature of bathing and arrival.

Original placement: the entrance

The sculpture was placed near the front of the Spa Hotel complex, close to the entrance sequence, when it opened in 1963. It served as a visual introduction to the experience ahead, signaling that this was not a conventional hotel but a place where art, water, and movement mattered.

Actress Mary Martin photographed beneath the iconic concrete-domed colonnade of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel, standing beside Bernard Zimmerman’s sculpture Dancing Water Nymphs. Images like this captured the Spa at its cultural peak—where architecture, public art, and celebrity converged at the heart of downtown Palm Springs.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

Center stage: the fountain

As the complex evolved, the Dancing Water Nymphs sculpture was relocated to the center of a reflecting pool, enhancing its dramatic effect. Rising from the water, the figures appeared animated by their setting, framed by the iconic colonnade and mirrored by the pool’s surface. For many visitors, this became the most enduring image of the Spa—a moment where sculpture, architecture, and water were inseparable.

The central mineral pool at the Palm Springs Spa Hotel, where water, architecture, and reflection worked together to create one of the city’s most memorable civic modernist spaces. This was where the Dancing Water Nymph sculpture was later relocated. The repeating domes of the colonnade form a dramatic backdrop.Courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / Palm Springs Life.

Where is it now?

Importantly, Dancing Water Nymphs was removed from the site prior to the 2014 demolition of the Spa complex. While its exact current location has not been publicly detailed in preservation records, the sculpture was not destroyed. Zimmerman’s works are held in museum and private collections, and the removal of the piece before demolition is widely acknowledged by local historians and preservation advocates.

Today, the sculpture lives on primarily through archival photographs and collective memory—its absence felt as keenly as that of the building it once animated.

Why it mattered

Like the Spa itself, Dancing Water Nymphs represented a moment when Palm Springs embraced civic art as part of daily life, not as an afterthought. It reinforced the idea that modernism in the desert could be sensual, playful, and human—qualities that continue to define why the Spa Hotel remains such a powerful entry in the Lost Palm Springs series.

From spa icon to casino-era evolution

As Palm Springs evolved, so did the Spa site. Tourism expanded, downtown priorities shifted, and the property became intertwined with later casino and resort development. Over time, renovations and additions obscured much of the original midcentury clarity.

According to preservation documentation published in Desert Magazine (September 2014) by the Palm Springs Preservation Foundation, the Spa complex had become a flashpoint—valued simultaneously as an architectural landmark, a sacred site, and an economic engine. Some preservationists thought the buildings had outlived their usefulness, while others upheld the integrity of the original design and its potential for restoration.

Demolition of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel and bathhouse complex, 2014Photo by The Desert Sun© Gannett / The Desert Sun

The demolition: a city divided

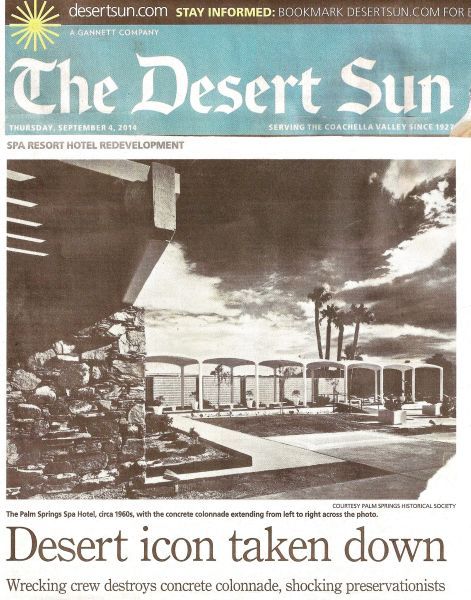

In 2014, the demolition occurred swiftly and was highly publicized.

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, as property owner, moved forward with demolition, citing the need to protect and preserve the Tribe’s sacred hot mineral spring and asserting sovereign authority over the site’s future.

The Palm Springs Spa Hotel and its iconic concrete-domed colonnade, photographed in the 1960s. The image ran on the front page of The Desert Sun on September 4, 2014, under the headline “Desert icon taken down,” as demolition of the Spa complex began.Photo courtesy of Palm Springs Historical Society / The Desert Sun.

Preservationists mobilized. As detailed in Desert Magazine and the Los Angeles Times, efforts included public appeals, letter-writing campaigns, and arguments that historic preservation incentives could support rehabilitation. The debate placed historic preservation and tribal sovereignty into direct—and very visible—tension.

The most shocking moment came early in the process: the demolition of the concrete-domed colonnade, the Spa’s most recognizable architectural feature. Spectators gathered to witness the dismantling of the structure, with many observing in disbelief.

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians who own the property, announced plans to demolish the Spa Bathhouse and Hotel in its entirety, and PS ModCom established a dialog and presented a case for restoration instead. In the midst of these discussions, the Tribe demolished the buildings in June 2014. (Lost Buildings - Palm Springs Modern Committee). The demolition date of the Spa Bathhouse and colonnade marked the end of an era for many.

A personal memory of the Spa

My own relationship with the Spa Hotel complex evolved over time. Long before the larger casinos arrived in Palm Springs, I remember visiting the casino at the Spa during a weekend desert trip in the 1990s. Housed in what felt more like a warehouse than a resort—certainly not part of the original midcentury structure—it was a long, low-ceilinged space packed wall to wall with people, with a thick cloud of cigarette smoke hovering above the gamblers. If memory serves, there was even a tent-like structure that functioned as an annex to the casino at the time. I remember walking through it and thinking, I don’t need to come back here.

That feeling changed later, after I moved to Palm Springs and was introduced to the spa itself and the ritual known as the “Taking of the Waters.” You could buy a monthly pass and return as often as you liked, moving through a sequence that felt almost ceremonial: eucalyptus steam rooms, dry saunas, soaking in the natural mineral baths, and finally a quiet meditative room to rest and reset. There was also a gym on site—where I first began working with a trainer—and later, a newer, more professional fitness facility was added. All of it is gone now, demolished along with the rest of the complex, but those experiences remain vivid reminders of how layered, contradictory, and deeply human the Spa Hotel once was.

What rose in its place

The story does not end with loss alone.

In April 2023, the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians opened The Spa at Séc-he as part of the Agua Caliente Cultural Plaza. The new spa intentionally recenters the site around the sacred hot mineral spring, reconnecting it to thousands of years of Indigenous history while presenting a contemporary, tribally guided vision for the future.

A private soaking room at The Spa at Séc-he, featuring mineral-rich hot water drawn from the same sacred spring that once anchored the historic Palm Springs Spa Hotel—now reinterpreted through a contemporary, tribally guided design.Courtesy of Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.

There’s no denying that the Spa at Séc-he has achieved global recognition as one of the nation’s finest spas. Its elegant private soaking rooms, quietly reminiscent of the original spa, make it a remarkable addition to Palm Springs. Even so, its creation came at a cost—the disappearance of one of the city’s most iconic and unforgettable architectural works.

The Spa at Séc-he, opened in 2023 as part of the Agua Caliente Cultural Plaza, reconnects the site to the sacred hot mineral spring that has sustained the Agua Caliente people for thousands of years.Courtesy of Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.

Why the Spa Hotel still matters

The Spa Hotel endures in Palm Springs memory because it sat at the crossroads of nearly everything that defines the city:

- Water in the desert — not as decoration, but as origin story

- Midcentury Modernism — expressed at a civic, public scale

- Tourism and identity — architecture as promise and spectacle

- Tribal land and sovereignty — reminding us Palm Springs' history runs far deeper than its postwar boom

That is why the Spa Hotel belongs in Lost Palm Springs.

This story joins others in the Lost Palm Springs series by The Paul Kaplan Group, that explore what the city has gained, what it has lost, and how architecture, memory, and identity continue to shape the desert we know today.

Editorial Note

This article draws from a combination of published journalism, preservation documentation, and historical records. As with many midcentury-era sites, some details reflect the best available archival sources and public accounts at the time of writing. Ongoing research and community knowledge may continue to add nuance to this history.

Sources & Further Reading

- Palm Springs Preservation Foundation“The Spa Hotel Complex” and Desert Magazine, September 2014https://www.pspreservationfoundation.org/spa-hotel-complex/https://www.pspreservationfoundation.org/pdf/Sep2014DesertMagazine_merged.pdf

- Los Angeles Times“Desert dust-up over demolition of tribe’s Spa Resort in Palm Springs”September 5, 2014https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/culture/la-et-cm-a-desert-dustup-about-demolition-in-palm-springs-20140905-story.html

- Palm Springs Life“Explore Palm Springs: Agua Caliente Spa and Hotel”https://www.palmspringslife.com/history/explore-palm-springs-agua-caliente-spa-and-hotel/

- Palm Springs Modern Committee (PSModCom)Lost Buildings: Palm Springs Spa Hotelhttps://psmodcom.org/lost-buildings/

- Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians / Agua Caliente Casinos“New World-Class Luxury Spa Destination: The Spa at Séc-he Now Open”April 2023https://aguacalientecasinos.com/press-release/new-world-class-luxury-spa-destination-the-spa-at-s%D1%90c-he-now-open/

Selling Your Home?

Get your home's value - our custom reports include accurate and up to date information.

.png)